Highway to Prison: The Illiterates

Highway to Prison: The Illiterates

When as many as 75% of inmates in our prisons are illiterate, and 85% of juveniles who interface with juvenile courts are illiterate, perhaps it is time to take a look at how the inability to read impacts lives and increases the population of prisons here and across the nation. Most inmates are at least “functional illiterates.” They understand the words on road signs, but they lack the ability to read and comprehend written instructions or even a brochure. Many cannot fill out an application, and training them in any skill must be taught by hands-on example.

It’s not that they aren’t smart. Illiteracy is learned, passed along by parents who cannot read or write, and according to studies by the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), one child in four grows up not knowing how to read in the U.S., three out of four food stamp recipients perform in the lowest two literacy levels, 90% of welfare recipients are high school dropouts, and 16 to 19 year old girls at the poverty level, with low literacy skills, are 6 times more likely to have out-of-wedlock children than their reading counterparts.

The study also reported that Black and Hispanic non-incarcerated adults have lower literacy scores than white adults outside or inside of prison. “This data is strong evidence that the U.S. educational system may be failing people along racial lines,” says NAAL. Meanwhile, we are consistently graduating high school seniors who cannot read a book written on an 8th grade level, robbing them of access to a successful life.

But there is hope.

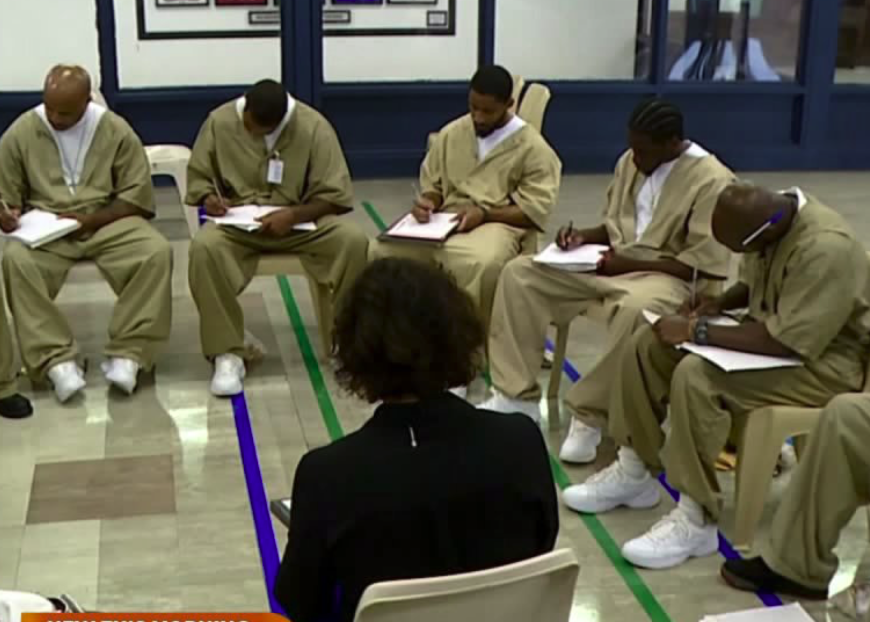

For more than two centuries we have used our penal systems to punish offenders. But more recently, the lights have gone on in the barn. Smart people have considered the fact that prisons can do more to help incarcerants, and might be able to mitigate causational factors that tend to lead to re-incarceration. Here in Indiana such an effort has been at work for some time. On any given day, about 1,100 people in Indiana prisons are in class. Some are starting at the beginning to learn to read, others are expanding their education to pass a GED test—the equivalent of a high school diploma. Everyone entering the Indiana prison system has a case manager, who offers and hopefully encourages the inmates to take advantage of the available opportunities.

Says Patrick Callahan, Director of Adult Education and Training for the Indiana Department of Corrections, “We run the spectrum from ‘can’t read’ all the way to those who made it to 12th grade but never received a diploma. It’s a school district that spans over 32,000 miles.” However, classes are optional. The old saying is true, “you can take a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink.” So, only those who want to learn or receive their GED attend classes, and that’s the sad part. Only about a quarter of those who could take advantage of the courses, do so. At 2nd Chance Indiana, we know that getting jobs and an income for reentrants is the #1 barrier to re-incarceration, but for those who reenter as confident readers, armed with a high school diploma—it’s a different ball game, where jobs are more plentiful and more lucrative.

Simply put, illiteracy is a disadvantage that makes people more likely to end up behind bars. So, let’s quit grooming kids for failure. Harry Truman once said, “Not all readers are leaders…but all leaders are readers.” Now, if only we could figure out a way to induce more inmates to take the classes they need,

Nancy